In light of discussion about inflation and slowing global growth in advanced economies, many are forgetting about the implications of these global macroeconomic conditions on developing economies. Whilst there have been major improvements and changes made to reduce inequality between economies over the last few years, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and United Nations (UN) express concern in two recent reports about whether current macroeconomic conditions are going to halt years of progress. This fortnight’s article will analyse how rising inflation levels and slowing global growth are disproportionately affecting developing economies, with a focus on the Sub-Saharan African region.

How is declining growth impacting inequality between developing and advanced nations?

After the release of last fortnight’s article, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development released a comprehensive report exploring how economies across the globe are coping with ongoing economic shocks, such as COVID-19, the war in Ukraine and rising interest rates across the globe. The UNCTAD’s outlook, however, is not very optimistic, describing the current global economic situation as being a “cascading and interconnected crisis”.

Notably, the report expresses serious concern about the potential of a “policy-induced global recession”, wherein the effects of rising interest rates and contractionary fiscal policy decisions across the globe are expected to result in a significant plunge in growth worldwide. The UNCTAC’s projections suggest that global growth will slow from 2.5% in 2022 to below pre-pandemic levels, falling to 2.2% in 2023.

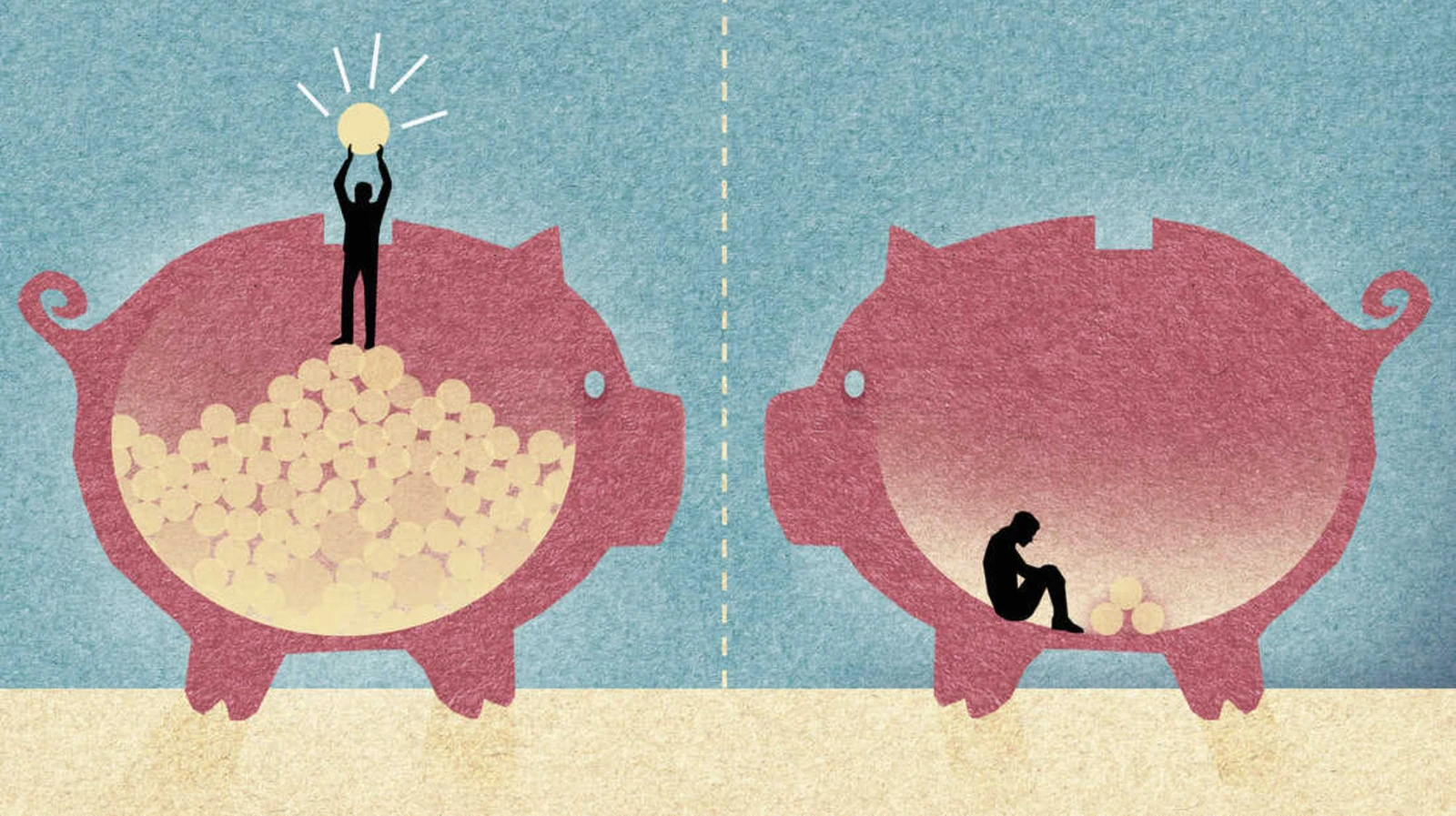

Devastatingly, the effects of this decline in GWP are expected to hurt developing economies the most. The report argues that growth rates in developing economies will fall below 3%, juxtaposing the 6% average growth rate that developing economies experienced in the 1990s and in the 2000s. In a time where sustainable development is of utmost importance and bridging the gap between advanced and developing economies is a paramount concern, the report implies that the effects of COVID-19 have hindered decades of attempts to minimise inequalities between nations.

In terms of income inequality, it is expected that this sub-par rate of growth will result in 58 million people in Africa falling into extreme poverty in 2022 alone. As a continent, Africa experienced significantly higher rates of poverty amidst COVID-19 than any other nation, with the World Bank estimating that 23 million people entered extreme poverty in 2020. Furthermore, it is expected that the actions of the Federal Reserve in the US will cut “an estimated $360 billion of future income” for developing economies, which is likely to increase as US interest rates continue to rise. Based on the targets released in September, it is likely that the Federal Reserve’s rates will reach 4.75%-5% next year.

To add on to the devastating effects of recent economic events, the report shows that 46 developing economies are “severely exposed” and 48 are “seriously exposed” to multiple economic shocks. Ongoing attempts to boost trade and financial flows to and from developing economies have brought the strengthened the international business cycle, yet exposed developing economies to more intense shocks through financial contagion. As a result, the report suggests that developing economies are facing “alarming levels of debt stress and under-investment”, with net capital flows to developing countries turning negative since 2021.

Looking for Economics coaching? Come enrol in Project Academy’s Economics classes!

Inflation is sky-high in Australia, but other countries are worse off

Turning our attention to the IMF’s World Economic Outlook for October 2022, rising inflation has been found to disproportionately affect developing economies. 2022 has been a significant year for price stability. Inflation in advanced economies reached its highest rate since 1982, with US inflation reaching 8.3% in August and Euro inflation reaching 10% in September. Yet, developing and emerging economies are facing a peak of 11% inflation in the third quarter of 2022.

Alongside the slowing growth rate, high inflation is said to have a more severe impact on lower-income groups in developing economies than any other group. This is because almost 50% of household consumption expenditure in developing economies is spent on food, which has driven approximately 40% of the annualised inflation changes in Sub-Saharan Africa. And with food prices accounting for a significant portion of inflation in 2022, this has devastating impacts on standards of living and quality of life, particularly for poorer nations.

According to the IMF, “global food prices remain elevated” due to the war in Ukraine, with wheat and corn experiencing significant price gains. Given that many low-income countries rely on wheat and corn as part of their diets, this aggravates issues relating to acute malnutrition and excess mortality. To make matters worse, Sub-Saharan Africa has significant exposure to new variants of COVID-19, despite having the lowest vaccination rates.

Thus, the combined effects of food inflation, slowing global growth and ongoing health concerns in developing economies should increase inequality between nations. Even though the output of developing economies is expected to be higher than advanced, inequality is expected to increase and remain an issue if macroeconomic conditions fail to stabilise in the next few years.