This year’s Budget has been an unprecedented continuation of the government’s heavy handed response to Covid-19. Across the numerous spending targets, fiscal stimuli and economic programs, the government has given us many statistics, trends, forecasts and plans to think about for this year’s HSC Economics. To make a little more sense of this large spending package, we need to break it down into areas of the syllabus we know and understand.

Firstly, we will examine the immense short term effects of the steep rise in Aggregate demand caused by the budgetary stimulus and the impact this might have on economic growth. As well what the low level of inflation means for the economy as a whole.

Secondly, we will go over the medium term implications of this budget on different areas of our economy, including possible changes to income and wealth distribution, increases to infrastructure spending and investment and what this all means for aggregate supply and income/wealth equality into the future.

Finally, we will deal with this budget’s long term effects on our external stability and current account, where concerns about government debt continue to loom as the growth in our public sector’s $980B cumulative debt shows no signs of diminishing.

All in all, this budget will have a sizeable impact on all areas of our economy right now, and into the future.

1. Short Term

As we know, any good essay starts with the immediate impacts of a policy and how things transpire in the economy across the short term. For a recap, the Covid-19 pandemic led to a steep short term decline in our economic objectives, with growth rates of -7% in Q2 2020 (1 October-31 December), deflation at -0.3% and seismic shifts in our labour market.

For example, the rate of underemployment (adults in the economy who are working but wish to be working more hours) rose by around 5% while the labour force participation rate fell by 2%.

Moreover, we had better than expected but still significant declines in employment, reaching peaks of around 6.5% unemployment in 2020. However it is important to remember that the unemployment rate does not take into account for jobless people who are NLF – “Not in Labour Force”; people who have given up on looking for work entirely, for example parents who have decided that there are no longer enough opportunities in the economy to justify spending time trying to find a job and have become stay-at-home parents.

The employment rate is calculated as: “100 x number of unemployed / labour force”, where “Labour Force = Employed + Unemployed” and Employed people work >1 hour of work a week.

As we might expect, if these economic issues were left alone without any government intervention, there would have been a long term decline in employment leading most consumers to spend less and save more, resulting in aggregate demand collapsing.

To respond to these issues, the government implemented the huge $90B “Jobkeeper” scheme, which helped firms retain employment and maintain a higher level of consumption throughout all sectors of the economy than if there was no government stimulus.

In this new budget, the focus has shifted away from “Jobkeeper” and towards Tax policy. Essentially, the government believes that future growth will be driven by improved consumer spending.

As you might recall from year 11 HSC Preliminary Economics, taxation acts as a leakage in the flow of income within our economy. By lowering the amount of tax payable, the government takes an expansionary approach, hoping to increase the disposable income that consumers have, hoping that they will spend the additional money throughout the economy.

These low and middle income tax cuts act as the centrepiece of this budget’s plan to raise consumption, for example the Treasury estimates that “extending the 2020 “Low and Middle Tax Offset” [LMITO] by another year will boost GDP by around $4.5 billion in 2022-23 and will create an additional 20,000 jobs by the end of 2022‑23.” The tax offset involves a tax cut of up to $1080 for single income-earners and $2160 for dual-income earning couples.

Source: https://budget.gov.au/2021-22/content/factsheets/download/factsheet_tax.pdf

For direct assistance with HSC economics, sign up to access our experienced tutors at Project Academy here: https://www.projectacademy.com.au

In terms of our essential economic issues, these tax cuts are combined with the continuation of the “Asset Write-Off Scheme” to help provide a large influx to our level of aggregate demand. By allowing firms to write off the full value of assets they purchase, the government incentivises investment in capital goods. Whether that means a small business buying a new truck to improve delivery times, or a multinational purchasing a suite of cars for their employees, the point and the impact is the same; goods and services will be demanded, and economic activity will increase.

In the short term, this will act as a complimentary inflow to aggregate demand along with the aforementioned improved consumption. Following this will be a rise in total economic growth and as demand increases, so will prices increase throughout the economy, driving a rise in overall inflation.

We are already starting to see the impacts of the government response in the economy, because inflation is back in the black at 1.1%, while GDP growth is +1.8% in Q1 2021/2022.

Moreover, unemployment has fallen and is now sitting comfortably at 5.6%, only 1% away from the NAIRU.

Source: https://www.pwc.com.au/federal-budget

Half of the 1.8% increase in GDP was driven by investment into capital goods [machinery and equipment] by the private sector, the strongest figure since the mining boom in 2009, and likely encouraged by the government’s “Asset Write-Off Scheme” (Source: Reuters via Nasdaq.com). This is further evidence that expansionary government tax policy is contributing heavily to support the economy following the effects of the pandemic and global lockdowns.

All in all the immediate effects of the budget look extremely positive.

2. The Medium Term

This budget is likely to have a variety of really important impacts in the coming years, ranging from structural change, to infrastructure, and income inequality; much of the Australian economy will be stimulated by investment outlined in this budget. In order to stand out against the rest of your peers in the HSC, it’ll help to analyse the less well-known policies and schemes in this budget in addition to the main trends and policies in this budget.

Income and wealth inequality:

In Economics, it helps to begin your essay with definitions of key concepts to demonstrate your understanding of the economic theories and ideas that you will be writing about.

Thus here are the definitions of income and wealth to distinguish between the two:

- Income relates to money being earned by a person/company, e.g. in return for selling a good or service or working for someone (labour).

- Wealth relates to the value of your assets, where your assets can be your real estate, possessions and the cash you have earned over the years.

Do not mix the two up! They are separate but related concepts!

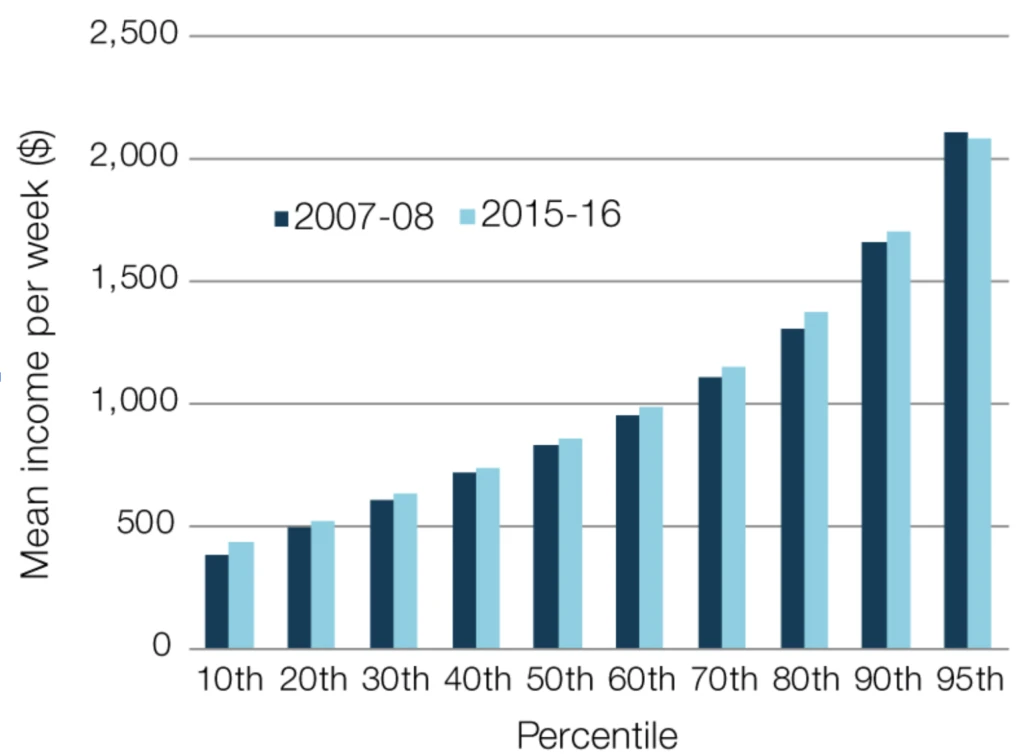

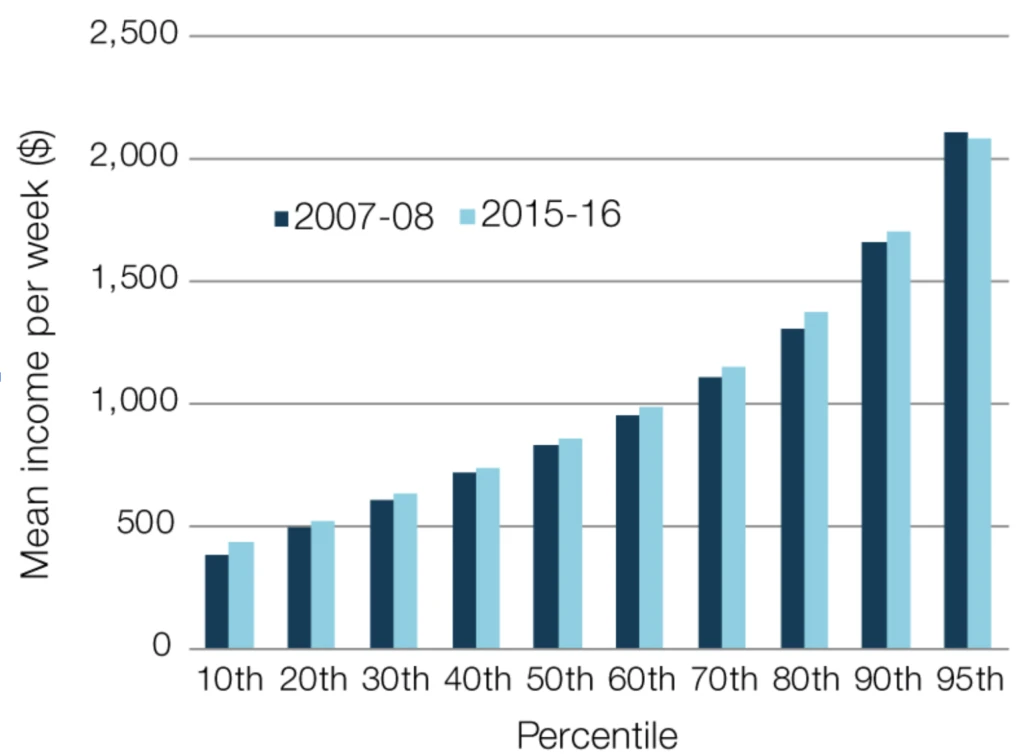

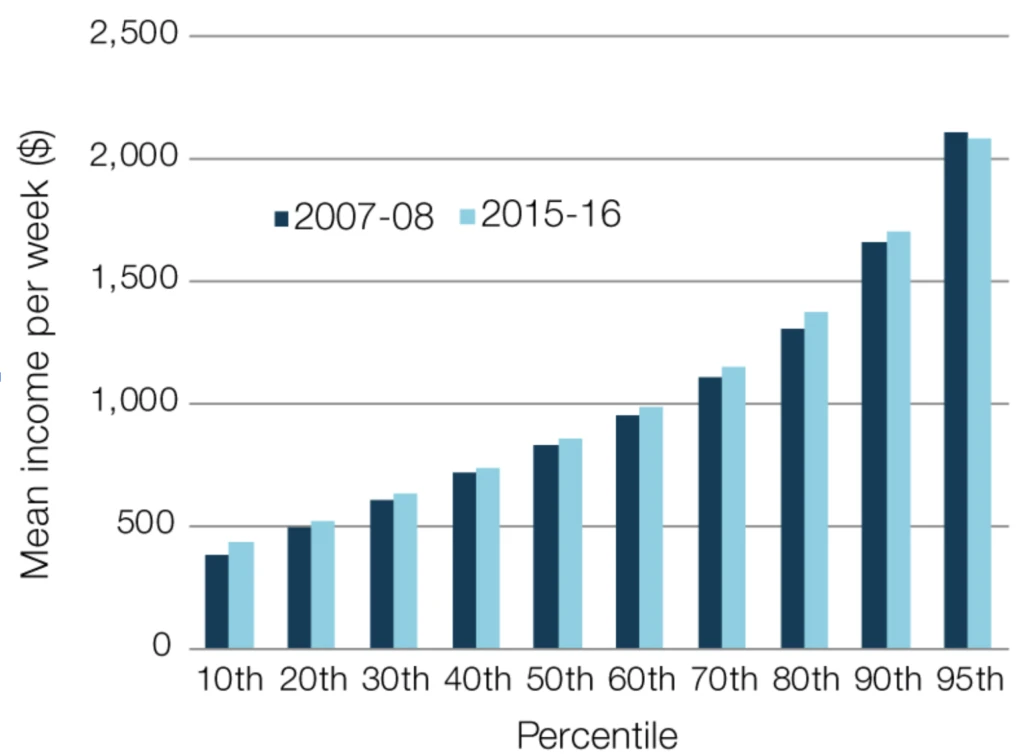

Income Inequality (measured by the income GINI coefficient or index) directly affects the level of consumption and aggregate demand in an economy in the short and medium term by affecting how many people have the immediate financial capacity to purchase goods and services. And lower income inequality is associated with higher GDP growth, because a higher GNI per capita means more people are able to buy more goods which are also more valuable at the same time, as evidenced by the fact that low income earners have a higher marginal propensity to consume (MPC) compared to high income earners having a lower marginal propensity to consume.

Income and wealth play a continued, often unrecognised role in strongly influencing rates of overall consumption, investment and other vital aspects of the economy. In this budget, the government has recognised wealth inequality as an increasingly serious issue affecting our economy. With a wealth Gini around 0.65, the wealthiest people in Australia owns a much larger portion of Australia’s total assets than the poorer Australians.

Source: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-11/federal-budget-2021-winners-and-losers/13328556

Wealth inequality (measured by the wealth GINI coefficient or index) means that during an economic boom and high-inflation period, the poorest people will benefit less than those who are wealthy, because they will profit much less from the increase in asset value/price, and instead be hurt by being forced to pay more for essentials such as a house.

During an economic downturn, wealth inequality means that the poorest people will suffer more than wealthy people, because as jobs are lost and wages decline, the poorest Australians will have less options to fall back on as secondary income sources, whereas wealthier people will have much higher incomes derived from their assets to sustain them through the recession.

For further reading and statistics, see “Investment Income” under “What are the components of income and wealth inequality?” http://povertyandinequality.acoss.org.au/inequality/

Moreover, it is only really those with assets and stores of wealth that have the capacity to save and invest, essential elements in driving the economy forward in the long term. Therefore this budget helps to change both the $8.1 Trillion housing market and $2.7 Trillion superannuation industry.

For example the changes to superannuation laws removing the previous $450 income threshold to be paid superannuation are very important to help increase the wealth and retirement savings for the poorest Australians and improve their quality of life.

In the short term, this helps to increase the sense of wealth held by the poorest Australians increasing the funds available for investment in the economy (superfunds are used to invest in the economy). In the long term, this enables the government to spend less money on welfare payments for those with the least capacity to build wealth and allocate this taxpayer money to other areas that need it!

Building on the changes to superannuation, the government has enhanced the existing and very important first home buyers grant. By allowing individuals to take a greater amount out of their superannuation (“super”) to purchase their first home, the government helps those with low stores of wealth (especially young people and under-35s) to buy their own real-estate, one of the safest and strongly appreciating asset classes.

By growing home ownership rates and equalising the distribution of home ownership, the government will help reduce the extent of wealth inequality, driving an reduction in all the negative impacts recognised earlier in our syllabus.

3. The Long Term

As we have come to realise, government spending is not without consequence. In order to fill in the huge decline in demand with its fiscal stimulus, the federal government has engaged with a variety of debt raising mechanisms. We will focus on the role of foreign debt and the Current Account. As of right now, the government’s total debt is creeping towards a trillion dollars, and $300 billion of that is debt owed to foreigners who bought the government bonds. As UNSW reports, government bonds were shared around the world with “Asia (excluding Japan) buying the second-biggest portion of government bonds (at 17.6 percent), followed by the UK (7.2 per cent)”.

In the long term, this has major implications for the economy; we will continue to see the outflow of debt servicing costs to foreign holders of our debt, a leakage of money worsening our Net Primary Income account and threatening to bring our current account surplus (which was achieved through an improved BOGS), back into deficit. Such a depreciation in the Current Account will worsen our future access to debt, because investors will be less and less likely to invest in our economy if it is increasingly unable to pay back debt. If Australia is increasingly unable to pay back its foreign debt, Australia’s External Stability will collapse. However, as we also know from the Pitchford Thesis; debt, if spent correctly will produce income that outweighs the debt, hence high levels of debt are not always such a death sentence for the economy.

An example of this budget’s forward-looking approach is its focus on infrastructure spending. The $15B scheme to improve Australia’s roads, bridges and dams will help to increase the mobility of resources, goods and services across the country, getting trucks loaded with goods from farms to ports faster, lowering the cost of production and price of our exports, and improving our international competitiveness.

In the long term, as we have seen with the scheme of motorways and infrastructure already built across the country, cheaper exports will help improve our balance on goods and services (BOGS) from the current $5b surplus to a more sustainable level for the long term. Therein, the government hopes to ensure that the Current Account surplus will continue into the future.

All in all, this budget gives us a lot to think about both now and into the future. When writing about it, be sure to think beyond the immediate statistics and trends and think well into the future when analysing what the government’s significant and broad spending in this budget means for the economy as a whole.

This series of weekly articles aims to compile the important economic news of the week into bite-sized summaries with HSC-specific takeaways. You can expect a new article every Monday!