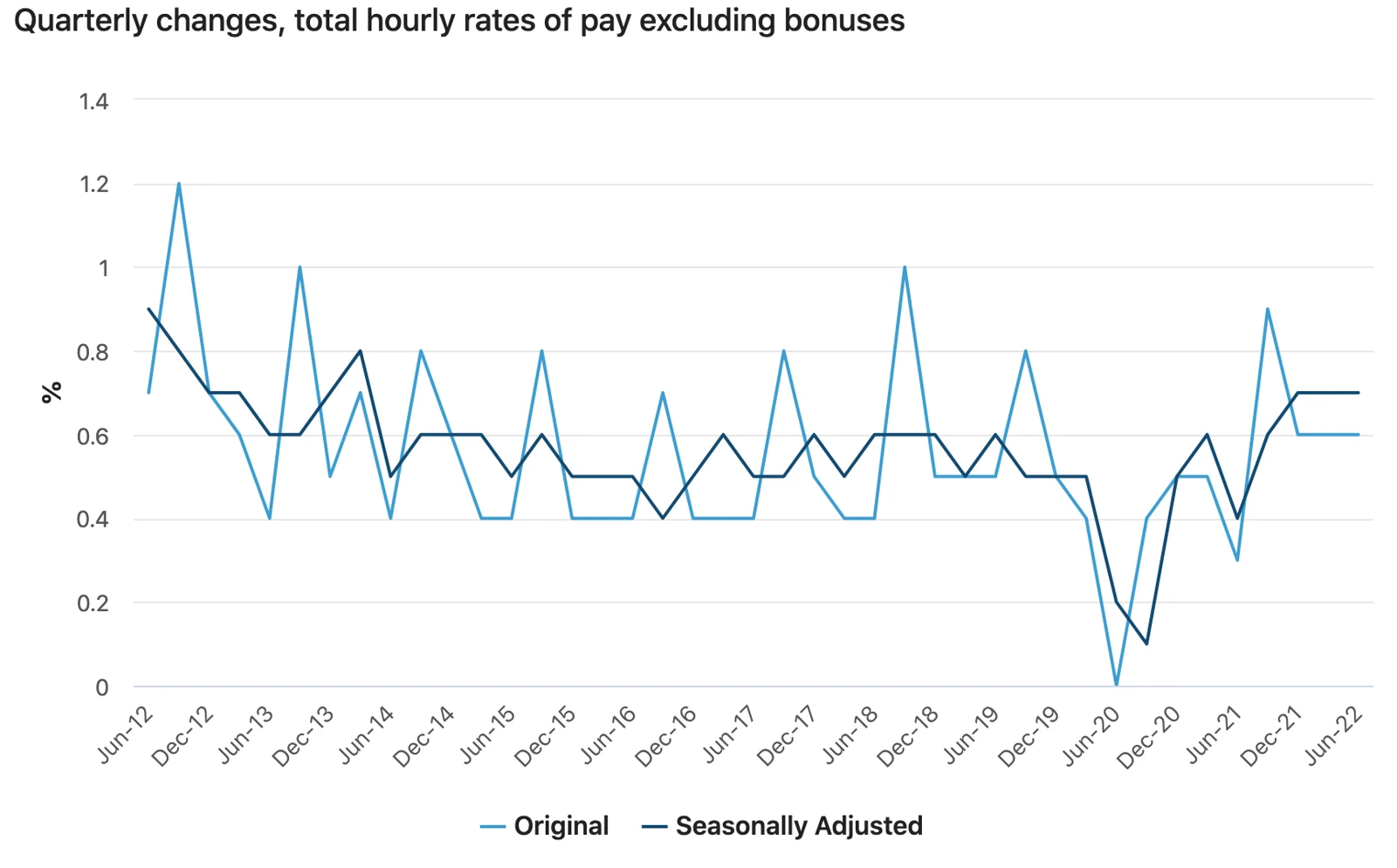

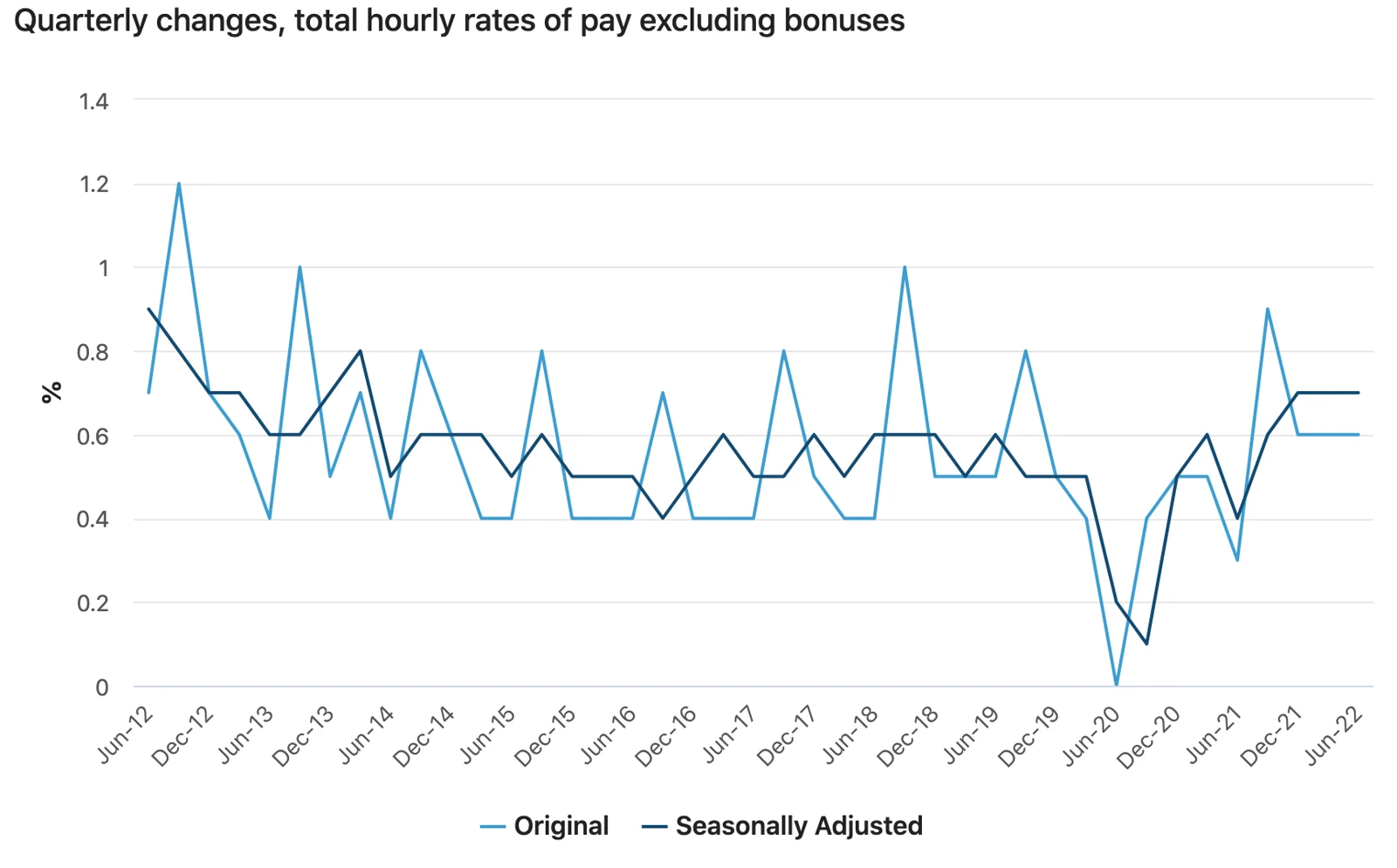

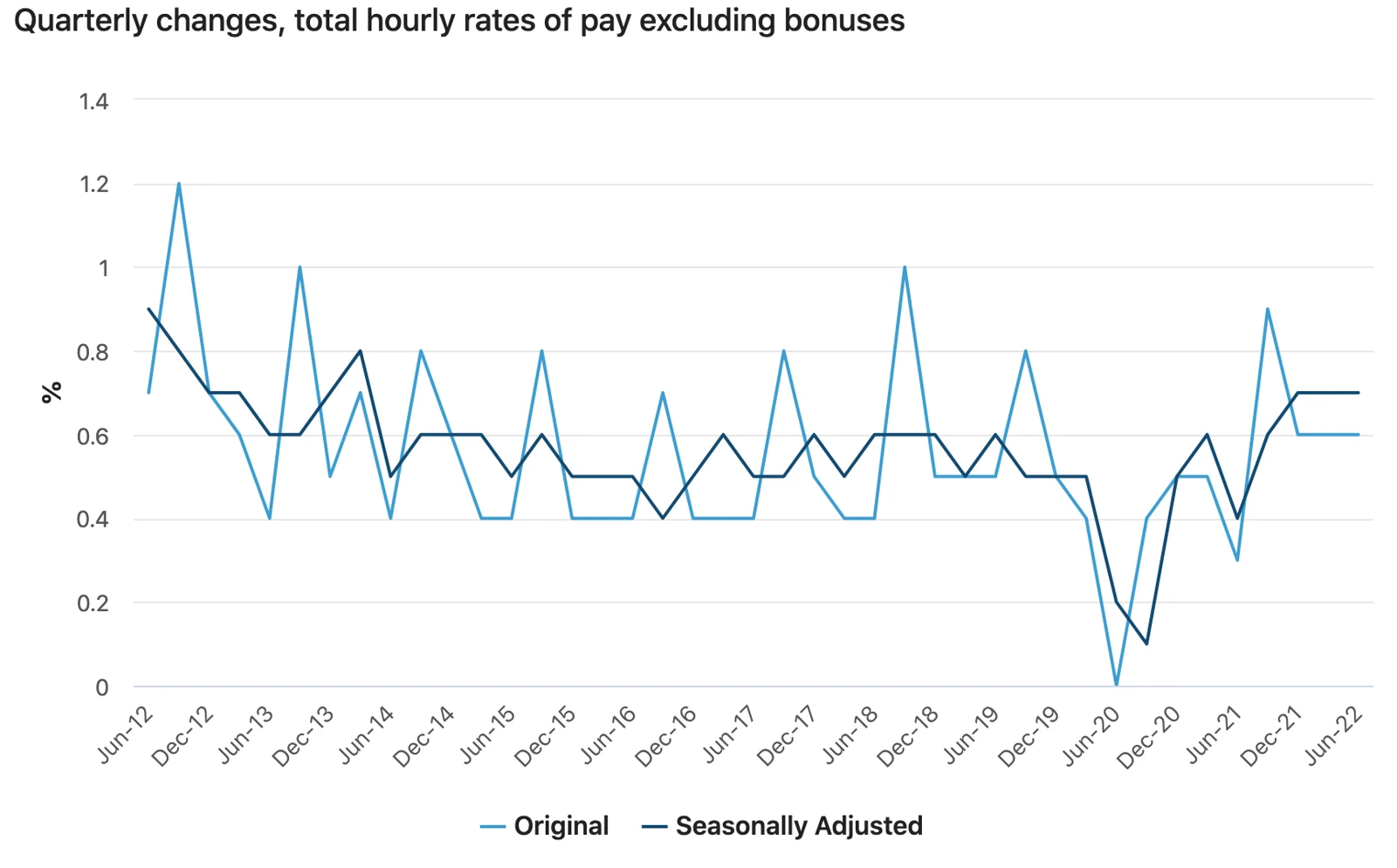

Since the last article, data about the wage price index and the rate of nominal wages relative to inflation has been updated to account for recent inflationary trends. Unsurprisingly, Australia’s real wages fell dramatically. Even though nominal wages experienced significant growth, the rate of inflation is far too high. This fortnight’s article will analyse the data released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the concept of real wages, the inequality created by nominal wage increases and explore the historical concept of ‘sticky wages’. As workers demand higher wages and inflation exceeds expectations, this article should become increasingly relevant over the next few years.

Wages don’t seem to be keeping up with inflation, no matter how hard we try…

Over the last few months, there has been an ongoing debate about the rate of inflation versus the rate of wage growth. As inflation reaches a high of 6.1% in June 2022, workers are urging the government to intervene and support low-income earners, as the cost of living soars and living in Australia becomes increasingly unaffordable. However, despite attempts to ease the cost of living via a higher minimum wage and contractionary monetary policy, inflation is yet to fall and real wages are yet to index to inflation.

It was recently reported that in the 12 months to June, wages grew by 2.6%. As noted by Greg Jericho, economist for The Guardian, this is the first time that wages have grown faster than 2.5% since 2014. Whilst this appears to be a good thing, it is hardly good news. Even though nominal wages have increased by 2.6%, inflation of 6.1% means real wages have fallen by 3.3 to 3.5% in the 12 months to June.

Furthermore, this nominal wage increase has disproportionately benefitted private sector employees, who saw wages grow by 2.7%, compared to the 2.4% growth experienced by the public sector. Despite this, employees in education and healthcare didn’t experience the 2.4% growth that the rest of the sector experienced. Education and healthcare workers only saw a 2.3% growth in nominal wages, despite ongoing demands for higher wages and an increased number of healthcare and education workers leaving the workforce entirely.

Not only did public sector employees find themselves at a disadvantage, but entire states and territories suffered more than others. Whilst NSW, the most populous state in Australia, experienced a -2.5% decline in real wages, every other state and territory experienced a larger decline in real wages. Western Australia saw a -4.4% decline in real wages, with the Northern Territory coming in at a close second with -4.3%. Notably, public sector workers in Western Australia were the most disadvantaged by the rising inflation rate. Public sector workers in Western Australia only saw 1.1% growth in nominal wages, despite record-high inflation.

Looking for Economics tutoring? Come enrol in our classes at Project Academy!

Arguably, it will take a long time for Australia to achieve a nominal wage increase that is perfectly indexed to the increase in inflation. This is largely due to the “sticky wages” paradox. This idea was first proposed by John Maynard Keynes, who introduced the idea of ‘sticky wages’. Keynes argued that employees are resistant to pay decreases, even if economic conditions are deteriorating and the economy is entering a recession. It is argued that during a recession, workers are increasingly likely to fight off a reduction in pay, as they have the flexibility of moving to another, higher-paying position and require additional funds to support themselves during a downturn.

As a result, firms will try and keep workers on the payroll and aim to cut costs in other areas of the firm. Therefore, when the economy exits a recession, the firm doesn’t have to worry about re-training and the additional costs associated with that process. Hence, it’s easier for firms to simply cut workers hours, keep them on the payroll and cut costs in other areas.

But how does this relate back to the idea of lower real wages? Because wages get ‘sticky’. Since the firm decided to prioritise their employees and cut costs in other departments, they are forced to hold off on future wage increases when the economy recovers, as it often becomes unaffordable for them to keep on increasing their employees’ wages.

Furthermore, there is a psychological element to the idea of ‘sticky wages’. Since nominal wages have increased by 2.6% and inflation has increased by 6.1%, we can assume that there has been a 3.5% real wage cut (inflation rate - nominal wages). However, if it were June 2020 where inflation was -0.3%, firms could achieve the exact same real wage cut by decreasing nominal wages by 3.8%. In both cases, the real wage cut is 3.5%. Yet, almost all workers would agree that the second scenario delivers a much greater psychological blow than the first scenario.

The point is, even if we have ‘sticky wages’, workers are generally satisfied with an increase to nominal wages and would prefer that to a pay cut, even if it meant real wages were declining. This idea of ‘sticky wages’ explains the real wage debacle that Australia has experienced throughout 2022 and will continue to experience for a while.