As some of you may have heard, China’s second largest property developer has announced that it may not be able to sell enough apartments to meet its looming level of debt. This week’s article will consider how this has come about, and the impacts on Australia’s economy. Additionally, the Federal Treasurer, Josh Frydenberg has publicly announced his support for Australia commit to net zero emissions by 2050, due to the economic benefits (or avoidance of economic detriments) associated with the commitment.

1. Evergrande on the brink of collapse

While Evergrande is China’s second biggest property developer, it is also the most indebted with liabilities (payments owing) totalling over US$400 billion. As the Chinese government has placed tighter restrictions on the real estate industry amidst the increasing level of debt in the sector, the company had to discount the price of apartments on sale to sustain financial flows and by extension its projects.

However this, along with what the company has termed as “negative media reports”, has prompted a reduction in creditor and investor confidence in the company. This has further constrained financial flows, causing Evergrande further financial stress. Yet, the company has not completely defaulted yet due to still being in a 30-day grace period on the payments it owes.

What are the consequences for the Australian economy?

Earlier on it was speculated that the collapse of the company would produce a “Lehmann effect”, similar to the collapse of the Lehmann Brothers bank that prompted the GFC in 2008. However, analysts such as those from Barclays believed that this would be unlikely because the Chinese government had already been monitoring the property developer giant’s situation for a number of months and the fact that local Chinese governments (equivalent to the Willoughby City Council) depend on the land sales tax such as those provided by Evergrande for 30-40% of their income.

Dr. Shane Oliver, AMP Capital’s head of investment strategy, reinforces this sentiment as he notes that allowing the company to go bankrupt would reduce a large fraction of Chinese households’ wealth and would go against the government’s objective of making houses more affordable within the country. Essentially, despite the Chinese government’s desire to make an example of Evergrande’s mistakes with excessive debt to other property developers, they don’t want the ordinary people to bear the burden.

However, Dr. Oliver also notes that “fears about Evergrande causing a global ‘Lehman moment’ have receded but we could still see more volatility over the next month or so. There could still be more bad news out of Evergrande before a restructuring occurs”. This sentiment somewhat holds true within Australia’s context. As mentioned in the HSC Economist a few weeks ago, Australia’s iron ore price has really taken a hit due to decreasing demand from China.

However, this is only exacerbated by the fall of Evergrande, as the real estate market makes up 29% of China’s economic output. However, in addition to this, banks have become even more strict in terms of lending money to property developers, deterring land developers from buying land, which also restricts taxation revenue which can be received by the aforementioned local governments (which were recorded to have US$5.5 trillion worth of debt in 2020), further reducing infrastructure spending. This along with lower levels of consumer confidence will ultimately lower demand for Australia’s iron ore, as China accounts for 70% of its purchases, and property developers within China make up half of that figure. While it is still quite early, the future value of iron ore prices remains to be quite unsteady.

2. Josh Frydenberg publicly supports a net zero emissions target by 2050

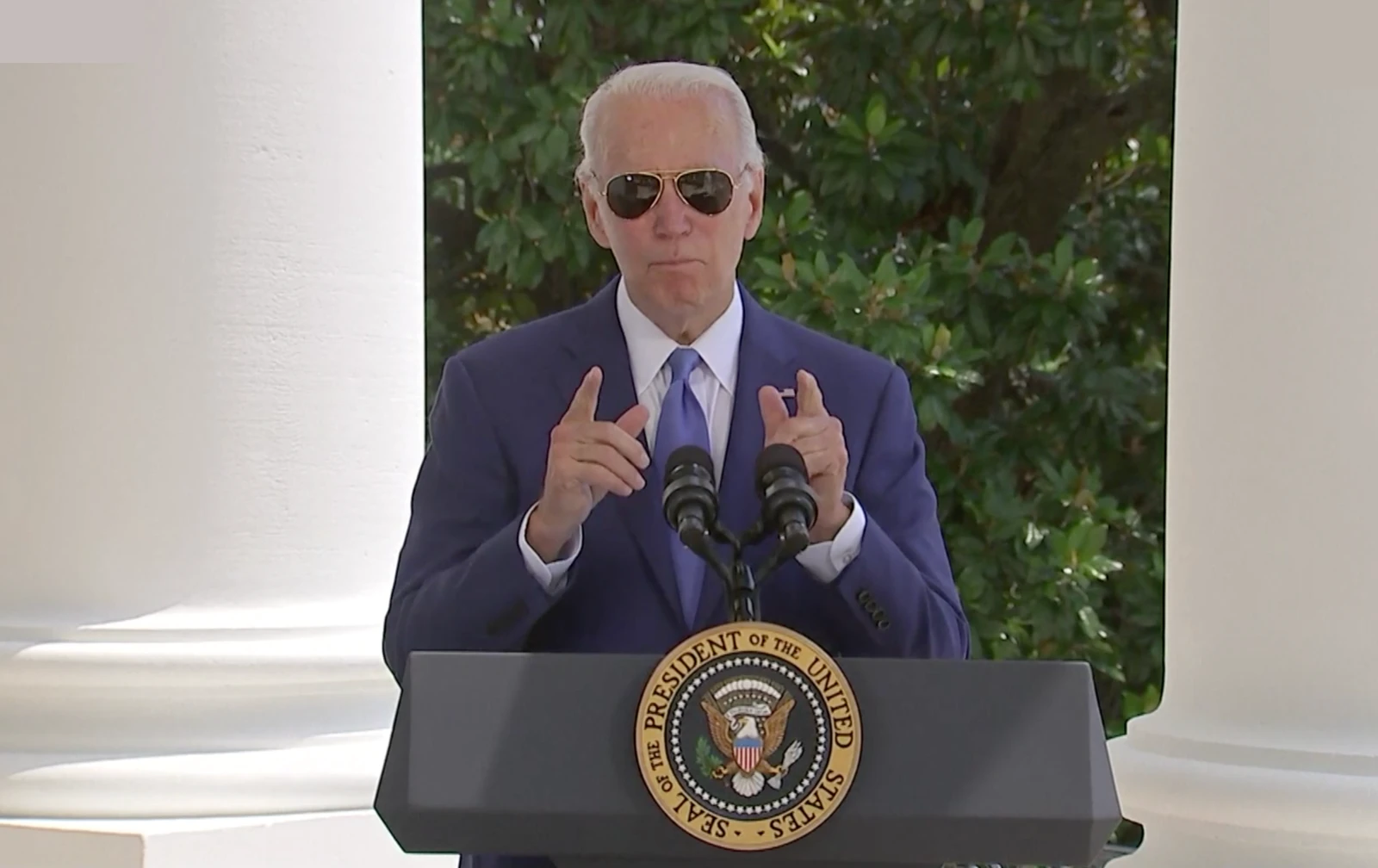

While Prime Minister Scott Morrison has reinforced that he would like to “preferably” meet the zero net emissions target by 2050, his government has yet to commit to the goal, despite increasing international pressure. However, ahead of the global climate change summit in November, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has announced his support for the target, due to the prospect of Australia being excluded and left behind as the rest of the world progresses closer to net zero emissions economies, noting that markets are becoming more and more receptive of the changing sentiment associated with climate change.

Frydenberg recognises that international opinion on Australia’s willingness to embrace a net zero economy will significantly influence Australia’s access to capital, as Australia is highly dependent on foreign capital for future growth, as well as the fact nearly half of Australia’s Commonwealth bond securities are owned by foreign investors. If investors believe that Australia is no longer a forward-thinking, innovative and advanced economy, they’ll cease investing in the Australian economy.

The treasurer emphasises that Australia’s lack of commitment to a clear target will potentially prompt Australia to be sanctioned by foreign investors and lenders, ultimately increasing borrowing costs, an impact that would be felt by consumers and small businesses as well. However, figures such as the former United Nations Security General, Ban Ki-Moon have noted that “Australia risks finding itself on the wrong side of carbon border tariffs as other nations move ahead, seizing the opportunities of the zero carbon age”. He echoes the notion that while other economies innovate and create new environmentally sustainable means of prosperity, Australia will not be able to enjoy these same benefits if it does not take necessary actions such as honouring its 2015 Paris Climate Conference commitments.

Source:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-09-24/treasurer-backs-net-zero-2050-target/100489434

Why has Australia not committed to the target?

Well, it comes down to the syllabus-specified limitation of policy making known as political constraints (apologies in advance for the political digression). It is important to note that Australia’s current government is a coalition, made up of both the Liberal Party and the National Party, with the former holding more power. However, for the coalition to commit to the net zero target, an agreement must be made between both coalition partners, but National Party members such as the deputy Prime Minister, Barnaby Joyce, have raised concerns about the net zero target and its consequences for the National Party’s voters, the majority of which work in the mining and agricultural sectors of the economy.

In particular, he is concerned by a potential surge in structural unemployment amongst his voters (which often occurs as an economy undergoes a major transition, for example the closure of the PMV sector), as well as the flow on impacts on indicators such as short term growth.

Josh Frydenberg (a member of the Liberal party), does indeed note that there will be risks that need to be managed, however, he also believes that the transition will produce long-term benefits for the economy, and has encouraged financial institutions such as banks to continue supporting the mining and agricultural sectors within the economy to help them transition to environmentally sustainable practices and operations.

What does this mean for the Australian economy?

For now, no commitment has been made, and thus it can be argued that there is a limited impact. However, while the federal government has yet to commit to a target, multiple states including NSW have adopted the target and have implemented policies accordingly. The treasurer’s comments have also highlighted the extent to which economies across the world are becoming increasingly integrated via globalisation, which forces countries to be more accountable for the consequences of their economic activity. Moreover, he has also made it clear there is desire within the government to realise the long-term benefits associated with the structural transition to a net zero economy.