1. Introduction to this Guide

Essays can be tough. Like, really tough.

They’re made tougher still because every HSC English module has a different essay structure, and no-one seems to have a consistent idea of what an ‘essay’ actually is (not to get postmodern on you!).

My name is Marko Beocanin, and I’m an English teacher at Project Academy. In this post I hope to demystify essay-writing and arm you with a “tried and proven” approach you can apply to any essay you’ll write in HSC English and beyond. In 2019, I completed all four units of English (Extension 2, Extension 1, and Advanced), and state ranked 8th in NSW for English Advanced and attained a 99.95 ATAR – so take it from me, I’ve written a lot of essays! Here’s some of the advice I’ve picked up throughout that experience.

2. My Essay-Writing Methodology

For us to understand how to write an essay, it’s important to appreciate what an essay (in particular, a HSC English essay) actually is. I’ve come to appreciate the following definition:

An essay is a structured piece of writing that argues a point in a clear, sophisticated way, and expresses personality and flair.

Let’s have a look at each of these keywords – and how they should inform our essay-writing process – in more detail.

3. “Arguing a point” means CAUSE and EFFECT

When most people study English, they tend to make huge lists of Themes, Values, Concerns, Quotes and so on. While this is a great exercise for collecting evidence and understanding your texts, it’s important to remember that your essay is not simply a theme summary or quote bank – you have to actually argue something!

And any argument needs a cause and an effect.

When you approach any essay question, it’s not enough to simply chuck in quotes/topic-sentences that abstractly relate to it. An internal checklist you could go through while reading a question might look like:

- What is the question actually asking me?

- What is my response to the question?

- Am I actually making an argument in my response, and not just repeating the question?

- What is my cause?

- What is my effect?

- How can I prove my argument?

It’s only at question 4 that quotes/analysis/topic-sentences appear. Your first step in writing any essay is to actually have an argument to prove.

Cause and Effect in Thesis Statements

To demonstrate what I mean by cause-and-effect, let’s have a look at a lower-band essay thesis on Nineteen Eighty-Four:

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell explores totalitarianism.

This sentence is a flat declaration of a theme. While it does identify totalitarianism, it doesn’t give any indication on what parts of totalitarianism Orwell explores, and what the actual effect of totalitarianism is.

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell explores the abuse of power in totalitarian regimes.

This one is certainly better, because it describes a specific element of totalitarianism that Orwell explores – but it’s still missing an actual argument about what totalitarianism DOES to people. A full cause and effect (and higher band) thesis statement might look like:

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell explores how the abuse of power in totalitarian regimes leads to a brutalised human experience.

This thesis explicitly outlines how the CAUSE (abuse of power in totalitarian regimes) leads to the EFFECT (a brutalised human experience).

There’s certainly still some ambiguity in this sentence – for example, what sort of human experiences are being brutalised? – and in an exam, you’d substitute that for the specific human experiences outlined in the question.

In general, whenever you see sentences like “Composer X discusses Theme Y” in your essay drafts, think about developing them into “Composer X discusses how Specific Cause of Theme Y leads to Specific Effect of Theme Y”.

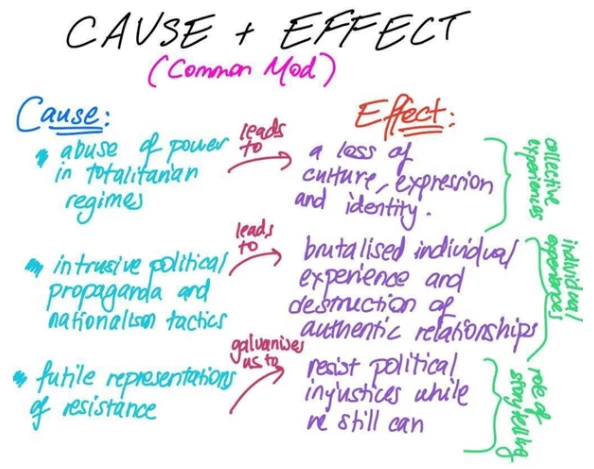

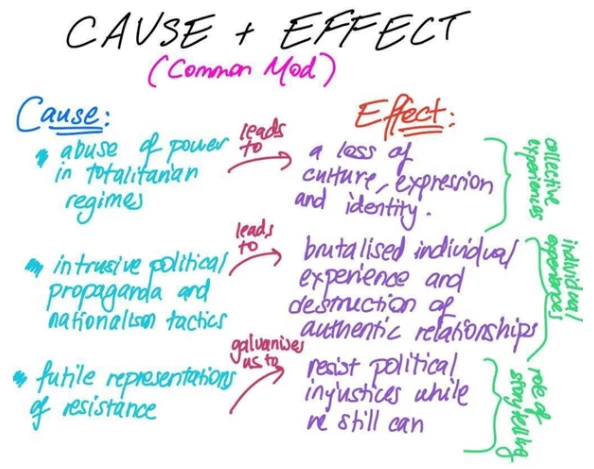

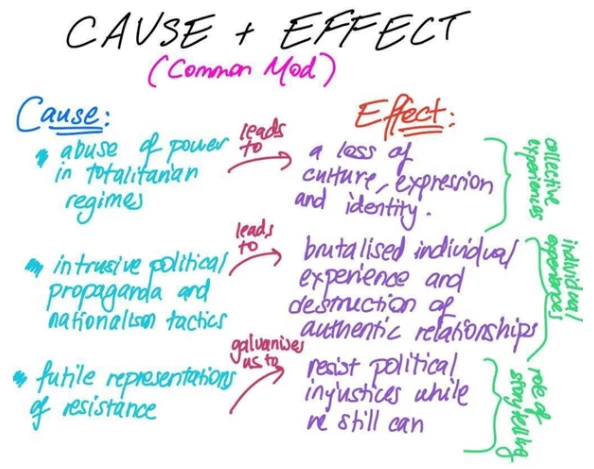

Cause and Effect Diagrams

To make sure that your arguments actually have a specific cause and effect, try writing them out in the following diagrammatic way:

Surprisingly, drawing the arrow made a huge psychological difference for me!

If you struggle with this, try to restructure/rephrase your arguments until they can be categorised in such a way. Making and rewriting these diagrams is also a great way to prep for exams without writing out your whole essay.

Cause and Effect in Analysis

Similarly, when it comes to your actual analysis itself, make sure that you’re not just listing techniques and quotes. You’re not just analysing your quotes for the sake of naming the techniques in them – you’re analysing them to prove a point!

Whenever you consider a quote for your essay, ask yourself:

- What is this quote about?

- How does this quote prove my argument?

- How do the literary techniques in this quote prove my argument?

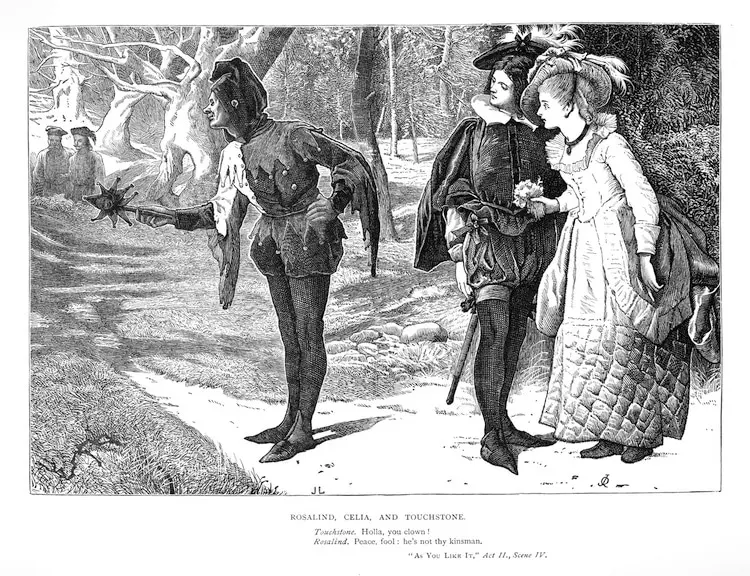

Let’s use an example from King Henry IV, Part 1 to illustrate this. A lower band piece of analysis might look like:

King Henry’s opening monologue employs anthropomorphism: “Daub her lips with her own children’s blood…bruise her flow’rets with…armed hoofs.”

While the technique of anthropomorphism is identified, this sentence doesn’t link to any argument about WHY that technique is there and what it does.

King Henry’s opening monologue anthropomorphises England as a mother violated by war: “Daub her lips with her own children’s blood…bruise her flow’rets with…armed hoofs.”

This is certainly better, because it explains what the technique actually does – but it still doesn’t discuss how the technique guides us to an actual point.

King Henry’s opening monologue anthropomorphises England as a mother violated by war: “Daub her lips with her own children’s blood…bruise her flow’rets with…armed hoofs…” to convey the civil unrest caused by his tenuous claim to the throne.

This analysis not only outlines the technique in detail, but it also explicitly embeds it with an argument – this time, structured as EFFECT (civil unrest) caused by CAUSE (his tenuous claim to the throne).

In general, whenever you see analysis in your drafts written as “Composer X uses Technique Y in Quote Z”, try to rewrite it as “Composer X uses Technique Y in Quote Z to argue Point A”.

4. Clear, Sophisticated Way

In general, clarity/sophistication in Advanced essays comes from two main sources.

4.1 Essay Structure

For most essays, the simplest and most effective overall structure looks like:

- Intro: Here, you answer the question with an argument, summarise your points and link to the rubric.

- 3 – 4 Body Paragraphs: Here, you actually make your points.

- Conclusion: Here, you re-summarise your arguments and ‘drop the mic’.

While it’s cool to play around with the number of body paragraphs, for example, the structure above is generally a safe bet for Advanced.

The most variety comes from the actual structure within your body paragraphs.

There are plenty of online guides/resources with fun acronyms like STEEL and PEETAL and less fun ones like PEEQTET – but ultimately, the exact formula you go with is a relatively inconsequential matter of choice and style. Just make sure you have the following elements roughly in this order!

4.2 Cause and Effect Topic Sentence

Here, you make your point as clearly as possible (remember cause and effect), and address the specific argument that the paragraph will cover. It’s fantastic if you can link this argument to the argument in your previous paragraph.

4.3 Context Sentence

This bit is vital (and often forgotten!). Texts don’t exist in a void – their composers had lives, were influenced by the world around them, and had inspirations and purposes in their compositions. Context can be political, socio-cultural, religious, philosophical, literary etc… as long as it’s there!

4.4 Cause and Effect Analysis

In a three-paragraph structure, a solid aim is for four to five quotes per paragraph. Each point you make should be justified with a quote, and each quote should have a technique linked to it. It’s usually helpful to order your quotes chronologically as they appear within the text (to show how the argument progressively builds) – but in more non-linear forms like poetry, for example, you can switch it up a little. Make sure each paragraph covers quotes from the whole text, to demonstrate a broad range of analysis!

Link

Here, you might give a restatement of your topic sentence that summarises your main ideas.

Wording and Expression

A common misconception with English Advanced is that huge words and long, meandering sentences will score the most marks.

In Advanced, clarity should come from your expression, while sophistication should come from your ideas. Ultimately, the more complex your expression and sentence structure is, the more your markers will have to work to connect with your content.

While an occasional well-executed piece of technical jargon is impressive, it should never come at the cost of clearly and explicitly getting your point across.

A few general tips I’ve picked up from both my time as a student and my work as a tutor include:

- Avoid using a thesaurus/online synonym-search whenever possible! If you didn’t consider using a word naturally, it’s unlikely it will flow with the rest of your expression.

- A long, comma-intensive sentence can (and should) almost always be replaced with two or more sentences.

- Use semicolons sparingly (if at all), and with GREAT caution.

- Never underestimate words like “because”, “leads to”, “causes” etc. They are simple, but brilliantly effective at establishing a clear cause and effect structure!

- Make sure to continuously reuse words from the question. Even if this feels clunky, it helps you actually engage with the question.

- Also make sure to continuously use rubric keywords – particularly in Common Mod and Mod A!

5. Personality and Flair

And now… the hardest bit. Putting a bit of you into your essays.

There’s no one way to “add personality/flair” – this is where you have the freedom to develop your own voice and style. Remember that your markers love literature – and for them to see real, unadulterated enthusiasm in your work is an absolute win that will be marked generously.

To develop that passionate flair/personality, I encourage you to do three things:Practice. A Lot. The more you write – whether it’s homework questions, mini paragraphs, or flat-out full practice essays – the better you’ll become at writing. It’s as simple as that.

6. Concluding Remarks

Get feedback on your work.

To make sure you’re actually improving with your writing, aim to get plenty of feedback from both of these groups:

- People who know your text and HSC English in-and-out (teachers, tutors, scholars etc.), so they can engage with your analysis and help develop your style/structure.

- People who don’t know your texts and HSC English particularly well (parents, friends, etc.), so they can check your arguments actually make sense!

Explore your own English-related interests.

Reading widely and writing weird stuff just for fun adds an indescribable but very real level of depth and nuance to your essay-writing. For me, this involved immersing myself in crazy literary theory that had nothing to with my texts, and writing super edgy poetry. Find what works for you!

Good Luck!!!

Whether this article reaches you the night before Paper 1, or at the start of your English journey – I’m confident that you can do this. If you can find even one thing that you connect with about this subject… whether it’s a character you love, or a beautiful poem, or a wacky critical piece that’s totally BS… hopefully you’ll realise that essay writing doesn’t have to be so tough after all!