When starting Module C, many students end up Googling “how to write a discursive”. Honestly, that’s probably how you ended up here.

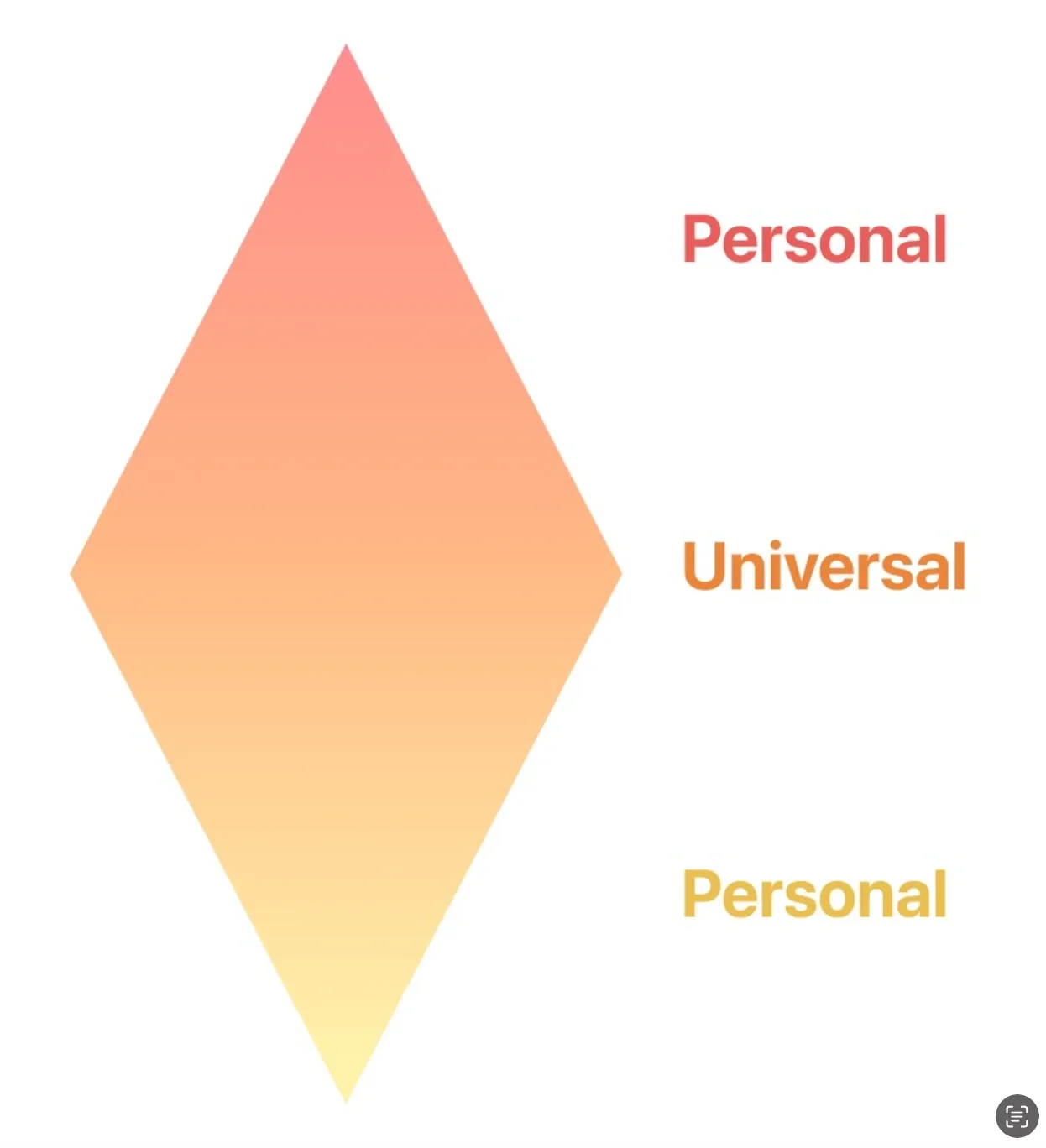

We can all agree that the rules of discursive writing are very confusing and seemingly contradictory. It needs to explore a particular topic, but without pushing an opinion! It’s meant to have a relatively informal tone, but make sure it’s not too informal! It’s meant to contain some figurative language, but ensure it doesn’t evolve into a creative! And as the cherry-on-top, the non-defined structure of discursive, makes the whole thing so much more confusing.

But don’t worry! This guide will take you through some key tips and tricks that help you write your own discursive.

Why you should write a discursive?

Before jumping into actual tips, our first tip is to take a step back. Don’t overcomplicate it too much. Out of all the text types you might choose to write in Module C (persuasive, informative, creative, discursive), discursive pieces are probably the most flexible. They’re free-flowing, giving you agency over how you write, and what you write about! You also don’t need to memorise quotes or do any analysis.

So, if an exam stimulus seems to be quite open-ended with many viewpoints, a discursive is a great way to explore these ideas.

With that in mind, let’s jump into the technicalities.

What is a discursive piece?

According to NESA:

Discursive texts are those whose primary focus is to explore an idea or variety of topics. These texts involve the discussion of an idea(s) or opinion(s) without the direct intention of persuading the reader, listener or viewer to adopt any single point of view. Discursive texts can be humorous or serious in tone and can have a formal or informal register. These texts include texts such as feature articles, creative nonfiction, blogs, personal essays, documentaries and speeches.

Now let’s break this down. A discursive piece first and foremost, is a discussion of ideas about a certain topic.

Picture this: You’re ranting to your friend about your favourite pizza flavour. Then along the way, you start discussing the best ways to make pizza. And then you might discuss the ethical nature of sourcing certain products attributed to pizza, and then you round up the discussion by talking about how pizza flavour preference correlates to personality (e.g. a no-fuss person might opt for a plain cheese pizza). You end off the discussion, with a striking realisation that everyone has their own preferences (not just with pizza, but with anything in life), because we’re all unique individuals, with our own identities.

You may be wondering, “how is discursive writing different to other text types?”.

NESA also explains some of the features specific to discursive writing. For instance, discursive texts often:

-

Explore an issue or an idea and may suggest a position or point of view

-

Approach a topic from different angles and explore themes and issues in a style that balances personal observations with different perspectives

-

Use personal anecdotes and may have a conversational tone

-

Primarily use first person although third person can also be used

-

Use figurative language or may be more factual

-

Draw upon real-life experiences and/or draws from wide reading

-

Use engaging imagery and language features

-

Begin with an event, an anecdote or relevant quote that is then used to explore an idea

-

Include a resolution that may be reflective or open-ended

Unlike with persuasive essays, you are not aiming to push a particular opinion or viewpoint. Unlike with an imaginative writing, you are not crafting a story with characters. Unlike with an informative piece, you are not trying to educate with non-fictional statements.

So, loosely speaking, discursive writing is intentionally-structured ranting about a random topic.

1. Brainstorming ideas

So how should you start? The first step is to find a topic which you don’t particularly care about (so you aren’t tempted to push a particular opinion/side - it’s not a persuasive essay), but a topic that is interesting enough to write about. I found these steps helpful:

-

List 10 - 15 ideas that seem interesting.

-

Create a shortlist by reviewing and eliminating ideas that are:

-

Too complicated to discuss in 1000-1200 words

-

Doesn’t give you the opportunity to explore multiple angles

-

Plain boring to write about

-

Hard to research, and you don’t know enough information about

-

-

Briefly research each topic in your shortlist, and narrow it down to the best one.

2. Structuring your discursive

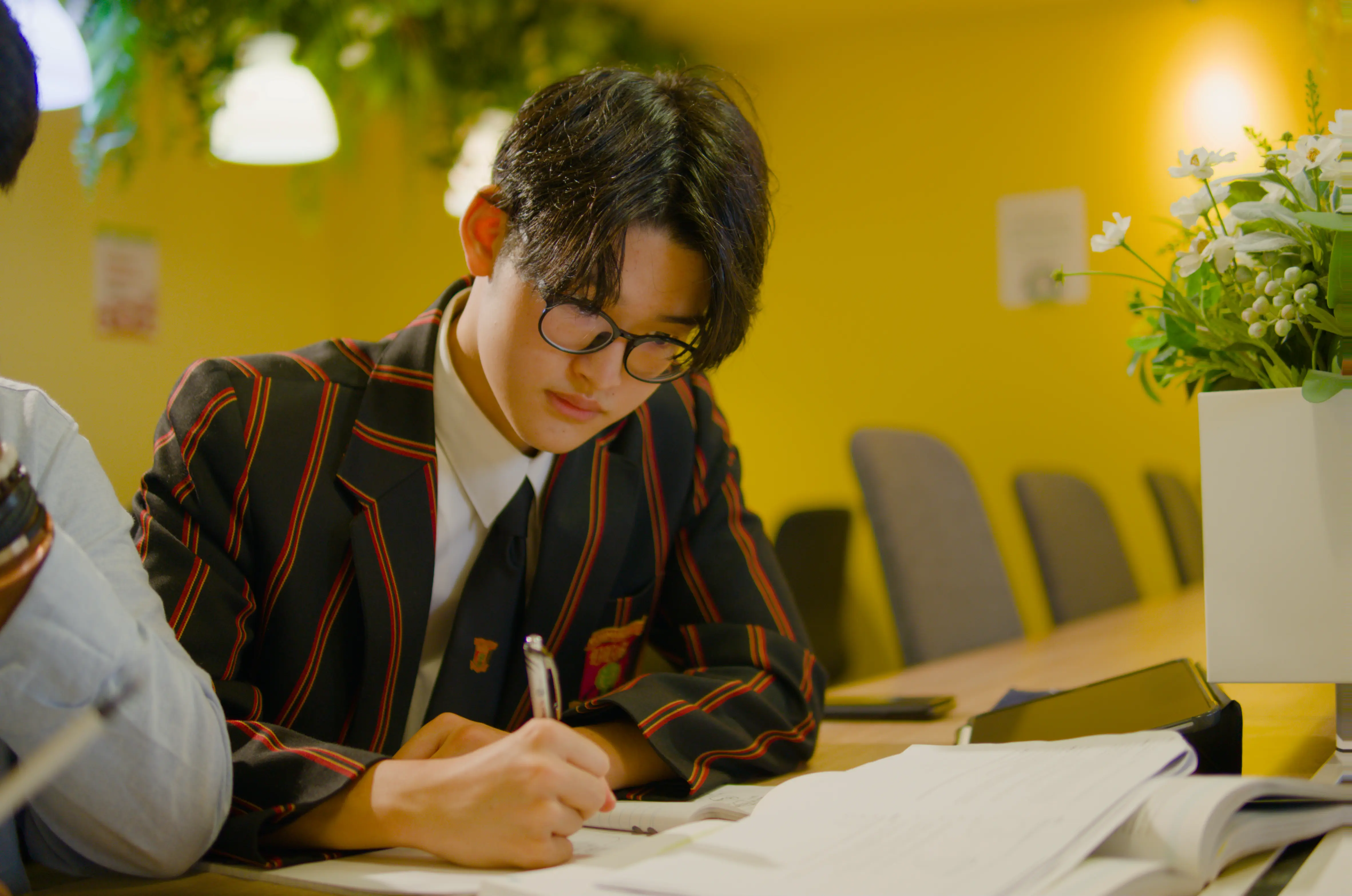

Unlike other text types, there is no “basic structure” or PEEL/PETAL to guide you. However, a diamond-shaped structure may help:

A suggested structure for discursive writing.

This signifies that you start with a personal anecdote (a short retelling of a personal experience - usually funny or interesting). Then, you branch out into a broader universal idea. Finally, tie it back in by referring to the same personal anecdote.

By doing this, your discursive essay will smoothly explore a train of thought without seeming like jumbled word vomit. The universal section also lets you explore other ideas and perspectives, which is crucial for a discursive response, according to NESA.

3. Using personal anecdotes

Unlike regular essays, discursive writing does not require you to integrate supporting evidence (e.g. quotes or literary analysis). In its place, we recommend that you use anecdotes (a feature of discursives, according to NESA). Why? They have two important benefits.

-

It allows the reader to form an emotional connection with you.

-

Niche personal experiences tend to act as a microcosm for something bigger. By introducing the anecdote, you’re encouraging the reader to reflect on the topic more broadly.

For instance, with the pizza example, the anecdotal retelling of YOUR favourite pizza flavour, eventually leads the reader to think about the concept of individual preference, and how everyone is different.

This then begs the question - what makes a good anecdote?

- Start with something random.

Many students fall into the trap of trying to find “the perfect anecdote”. However, ANY personal experience can be a good anecdote, from the most mundane encounter with your local barista, to a life-changing conversation with a famous person.

Don’t take it too seriously! Instead, think of something random, and then see if you can link it to your discursive idea.

Often, an exercise I would do with my English class at Project Academy, was to use a random word generator. We would then begin our discursive essays with an anecdote based on that concept.

- Choose an anecdote that also acts as a metaphor.

Ideally, you’re able to extract a metaphor from the anecdote, to weave throughout your discursive piece.

An example of this is seen in Margaret Atwood’s 1994 speech, “Spotty Handed Villainesses” (yes, I’m sorry to pull out the prescribed texts). Atwood compares the anecdote of watching a play about breakfast, to the value of literature within our life. If this metaphor doesn’t make sense, I highly encourage you to go read it!

By drawing comparisons between our personal lives to the idea being discussed, you’re adding a layer of complexity to your discursive essay. These extra details are what pushes a Band 5 discursive into the Band 6 region.

Let’s see this in action!

I’ve attached an example below, where I started my discursive talking about definite integrals, and then linked that to the value of literature (bizarre, I know, but it works).

Example: An anecdote on Definite Integrals

I think you would wonder why I have named my piece after a mathematical concept so niche, that it has no relevance in English. Well, except for one.

Definite integrals are designed to estimate, but also to definitively find the area of a curve. And how does it do this? Through rectangles. Yes, rectangles. In Maths class, I learnt that this simple, straight-edged, four-sided shape could be used to find the area under the most complex curves one could possibly think of. I thought to myself, “whoever invented this is a total GENIUS!”.

I was impressed that the solution was so out-of-the-box. But I was even more impressed that the answer to such a complex problem, rested on something so simple.

Now, when I struggle to uncover the meaning within an English text I’m studying in class, trying to decipher what the author wanted us to realise, I simply consider rectangles. I try to step outside the box of literal meaning. Instead, I holistically take the text as a rectangle, to understand the values, characters, ideas, and representations within the text.

4. Branching out to a “universal” perspective

This section forms the “body” part of your discursive essay. Here, it’s important to take multiple perspectives on the topic that you’re discussing.

Alternative perspectives can be interjected in many ways, they can be introduced through a book, a notable person in that field, a journalist, general statistics, or even through your own ideas! According to the NESA excerpt mentioned earlier, you can get these other perspectives, from “wide reading”. Often good discursives will contain a mixture of these tools.

REMEMBER: your discursive should not present these ideas as “for vs. against” a certain topic - this is not a persuasive essay. An effective discursive will consider the different viewpoints, without pitching them against each other.

Think of it like a spectrum of ideas rather than just 2 opposing ideas about a topic.

Another key tip is to ensure between each idea or perspective has a smooth transition, to create flow. To do this, use a conversational tone to direct the reader through each key point (as if you’re speaking to a friend), or use your established metaphor to link between different sections.

5. Get inspiration by reading other discursives

The best way to improve discursive writing is to read a LOT of discursive texts.

In doing so, you can get a sense of voice, and writing style, which you can mirror in your own writing. This is also why reading your friend’s discursive is so mutually beneficial - you get to develop your discursive-writing skills, while they get to hear feedback!

PS: The Project Academy Books app (a resource database, home to hundreds of files and other goodies) has heaps of discursive essays to read through. Those enrolled in their HSC English course also receive access to unlimited marking from experienced tutors, who can provide valuable feedback to drafts.

Where to find examples of good discursive writing?

-

NESA’s prescribed list of texts for “Module C: The Craft of Writing”, including:

-

Geraldine Brooks’ ‘A Home in Fiction’

-

Margaret Atwood’s ‘Spotty-Handed Villainesses’ speech

-

-

Newspapers, such as Sydney Morning Herald (and other places publishing “political writing” pieces)

6. Writing a conclusion

As mentioned in our previous discussion, the “universal” section is followed by a link to your original anecdote, guiding the reader back to a more “personal” perspective. A nice way to conclude the long train of thought in your discursive, is to finish in ambiguous, and open-ended way.

The goal is to prompt the reader to think about what you’ve discussed, and form their own opinions.

For example, this excerpt below is from a discursive about how society has forgotten the value of literature, because of other entertainment options. Earlier in the discursive, a personal anecdote was introduced, about borrowing a friend’s book, and then forgetting to read it for 6 months. Notice how it flows from a “wider” angle, to a more personal ending.

In our modern world, we need stories more than ever before. To re-ground us, and to remind us of who we are. After all, our personal narratives and identities are a mere amalgamation of our experiences, a mere compilation of snippets in time, begging to be preserved in ink. That’s what it means to be human. Whilst I say all this, another Netflix movie blares from my laptop, with retrospectively mediocre characters and a strangely predictable plotline. Perhaps it is time to pick up Charlie’s novel and read it.

Conclusion

I hope this discursive guide helped!

Remember: there are no real rules when it comes to discursive essays. Whilst that seems like a bad thing, it’s actually GREAT for you. Don’t get too caught up on what the “perfect” discursive looks like. Be creative, write using your own style and voice, and talk about whatever you want!

The best way to get good at this, is just to start writing.

Good luck!